Currently I am reading the book INNOVATORS by Walter Isaacson.

So today’s random thought arises from that book

In today’s world where science is questioned at least in the biological arena, I was struck by his discussion on the origins of the personal computer. Fortunately, we appear believe in the science related to technology, we use it daily and are hard put to deny its reality. How can we not? It fits in our hand; it sits on our desks it is in our refrigerator; it is on our car dashboard and can take up as much as 20 square feet on our living room wall.

One of the references in the book was to an article in the Atlantic magazine in 1945. Titled As We May Think was written by Vannevar Bush. The opening statement states the basis of his article. “Consider a future device … in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.”. Strikingly familiar? I am using this “device” as I write. Working on a “future device” envisioned over 75 years ago. A vision that was built upon theories and inventions nearly 200 years prior. Still do not believe in science. Or its value?

Before I start let me provide some background on Vannevar Bush he was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all wartime military R&D was carried out, including important developments in radar and the initiation and early administration of the Manhattan Project.[ SOURCE: Wikipedia] As Director of OSRD, Dr. Vannevar Bush coordinated the activities of some six thousand leading American scientists in the application of science to warfare. (Sometimes referred to as World War II). In that role he coordinated the activities of approximately 6000 leading scientists. Now in this article he challenges them to turn to the massive task of making more accessible our bewildering store of knowledge. Appropriate to today? In my opinion, yes. I believe it is always a good thing to be informed of how the journey from point A to point B is achieved. Maybe more importantly what was the idea that led to the start of that journey.

Science has provided the swiftest communication between individuals;

it has provided a record of ideas

and has enabled man to manipulate and to make extracts from that record

so that knowledge evolves

and endures throughout the life of a race

rather than that of an individual.

As a photographer Bush’s discussion on the future of photography caught my interest. “…The camera hound of the future wears on his forehead a lump a little larger than a walnut. It takes pictures 3 millimeters square, later to be projected or enlarged… the lens is of universal focus, down to any distance accommodated by the unaided eye” Can you spell bodycam? Now available from Amazon from hundreds of distributors.

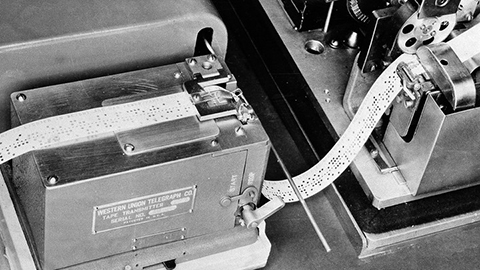

Let’s look at Bush’s examination of a more common task of shopping. “… Every time a charge sale is made, there are a number of things to be done. The inventory needs to be revised, the salesman needs to be given credit for the sale, the general accounts need an entry, and, most important, the customer needs to be charged. … The salesman places on a stand the customer’s identification card, his own card, and the card taken from the article sold…. When he pulls a lever… machinery at a central point makes the necessary computations and entries, and the proper receipt is printed for the salesman to pass to the customer.” Again, sounds familiar?

When I think about the article I’m writing? “…One might, for example, speak to a microphone, in the manner described in connection with the speech-controlled typewriter.” Today, I write this article with voice recognition software that will create a document that can be printed on paper or digitally.

But let me end at what should have been the beginning, again in his words –

“Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, “memex” will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.

It consists of a desk, and while it can presumably be operated from a distance, it is primarily the piece of furniture at which he works. On the top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. There is a keyboard and sets of buttons and levers. Otherwise it looks like an ordinary desk.

In one end is the stored material… only a small part of the interior of the memex is devoted to storage, the rest to mechanism. Yet if the user inserted 5000 pages of material a day it would take him hundreds of years to fill the repository, so he can be profligate and enter material freely.

Most of the memex contents are purchased on microfilm ready for insertion (CD, DVD, thumb drive, direct download). Books of all sorts, pictures, current periodicals, newspapers, are thus obtained and dropped into place. Business correspondence takes the same path. And there is provision for direct entry. On the top of the memex is a transparent platen. On this are placed longhand notes, photographs, memoranda, all sorts of things. When one is in place, (scanner) the depression of a lever causes it to be photographed onto the next blank space in a section of the memex film, dry photography being employed. (Digital printer, PDF)

There is, of course, provision for consultation of the record by the usual scheme of indexing. If the user wishes to consult a certain book, he taps its code on the keyboard, and the title page of the book promptly appears before him, projected onto one of his viewing positions. Frequently-used codes are mnemonic, so that he seldom consults his code book; but when he does, a single tap of a key projects it for his use. Moreover, he has supplemental levers. On deflecting one of these levers to the right he runs through the book before him, each page in turn being projected at a speed which just allows a recognizing glance at each. If he deflects it further to the right, he steps through the book 10 pages at a time; still further at 100 pages at a time. Deflection to the left gives him the same control backwards.

A special button transfers him immediately to the first page of the index. Any given book of his library can thus be called up and consulted with far greater facility than if it were taken from a shelf. As he has several projection positions, he can leave one item in position while he calls up another. He can add marginal notes and comments, ….”

Thereafter, at any time, when one of these items is in view, the other can be instantly recalled merely by tapping a button below the corresponding code space. Moreover, when numerous items have been thus joined together to form a trail, they can be reviewed in turn, rapidly or slowly, by deflecting a lever like that used for turning the pages of a book. It is exactly as though the physical items had been gathered together from widely separated sources and bound together to form a new book. It is more than this, for any item can be joined into numerous trails.

His “trail” is today’s Google search. “…Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified. The lawyer has at his touch the associated opinions and decisions of his whole experience, and of the experience of friends and authorities. The patent attorney has on call the millions of issued patents, with familiar trails to every point of his client’s interest. The physician, puzzled by a patient’s reactions, strikes the trail established in studying an earlier similar case, and runs rapidly through analogous case histories, with side references to the classics for the pertinent anatomy and histology. The chemist, struggling with the synthesis of an organic compound, has all the chemical literature before him in his laboratory, with trails following the analogies of compounds, and side trails to their physical and chemical behavior.

I will also conclude., First, a thanks to Vannevar Bush who both challenged and inspired the scientific community with his vision of the future. An additional thank you to Atlantic magazine published his article and now maintains a copy in electronic archives that provided the basis for this blog.

To my readers, let’s remind our friends, family and neighbors of what science has provided us. There is nothing “fake” about science. There may be disagreement about the outcome , product or prediction, but the scientific method is based on facts, not political philosophies.

Thanks for reading

More Stories

Remembering Red Bank Catholic Teachers

A POET TO CONSIDER